Eco Ganesh survey 2022 / पर्यावरणीय पूरक गणेश उत्सव अभ्यास

A survey of awareness was carried out by eCoexist as part of the Eco Ganesh campaign building up to the Punaravartan efforts in 2022 primarily in Pune city to check whether there was a willingness in the public to recycle materials during and after the Ganesh Chaturthi festival.

Initially the survey was sent out as an online Google form amongst a known network however after the first 500 odd entries we recruited the students of Fergusson college to go door to door to fill out the form with residents, Specific instructions were given to approach areas of high Maharashtrian population who are more traditionally celebrating the festival.

The intention of the survey was to check on the perspective of the public on various aspects of the Ganesh worship and ritual of immersion , to gauge how consciously they chose materials and products in the festival.

See the form used for the survey here https://forms.gle/Yt6nLuZJ2xs5TxRm7

A total of 1569 responses were collected. A significant difference was seen between the first online data collected versus the inputs from the students and this can be seen in the data analysis. Dr Sonya Sachdeva, a research social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, advised on data analysis to check for correlations and draw conclusions. Presented below are the visual analysis of the responses for each question followed by the final conclusions shared by Dr Sachdeva. For each question the rationale behind the question has been presented as well as possible conclusions that could be drawn from the responses.

Disclaimer: The target audience was primarily citizens who are already choosing to immerse their idols at home and so this creates a bottomline on the basis of which the differences in other choices are relative.

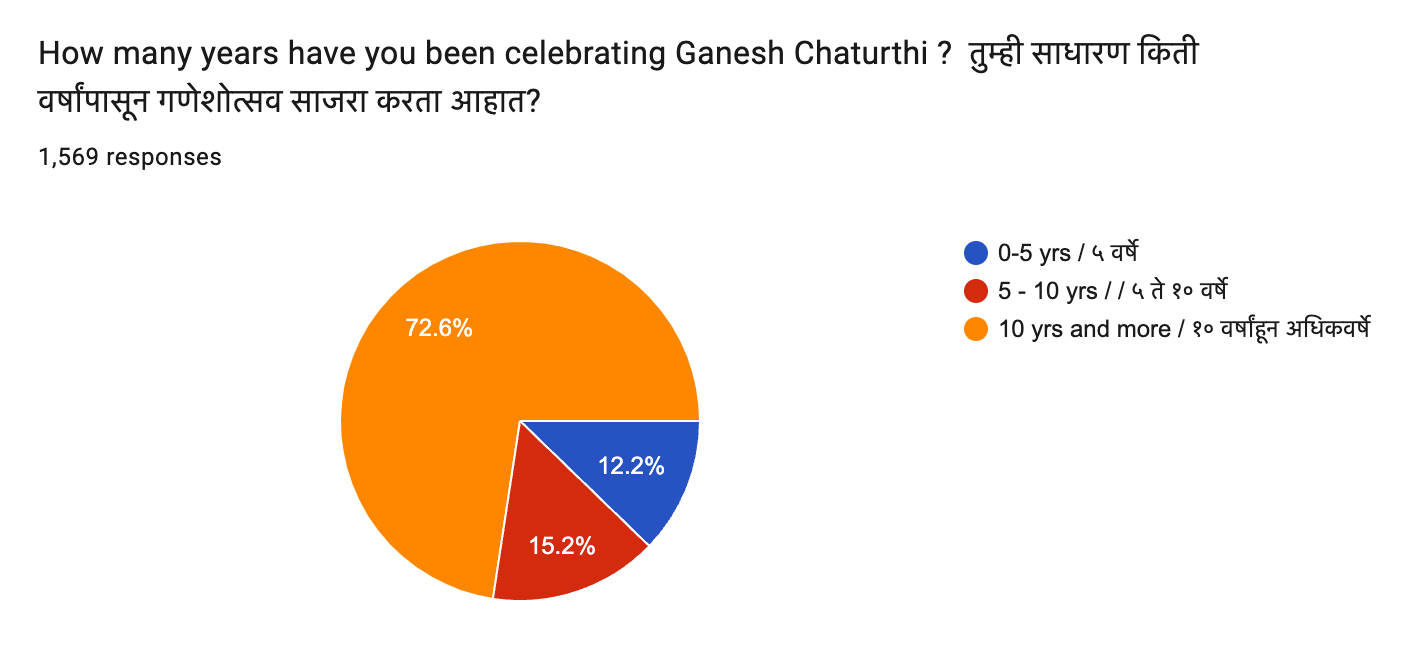

Q1: How many years have you been celebrating Ganesh Chaturthi ?

Assumption: The festival of Ganesh Chaturthi is a tradition in most Maharashtrian families and became especially significant by the invitation of Shri Bal Gangadhar Tilak even though the worship of Ganesha preceded this event by many centuries. For other communities in a more cosmopolitan urban milieu the festival is more of a social event more recently incorporated into their family get-togethers. Are traditional users more or less open to changing the ritual to make it more eco friendly?

Responses: Nearly three quarters of the respondents are traditional users having celebrated the festival religiously for over 10 years or more.

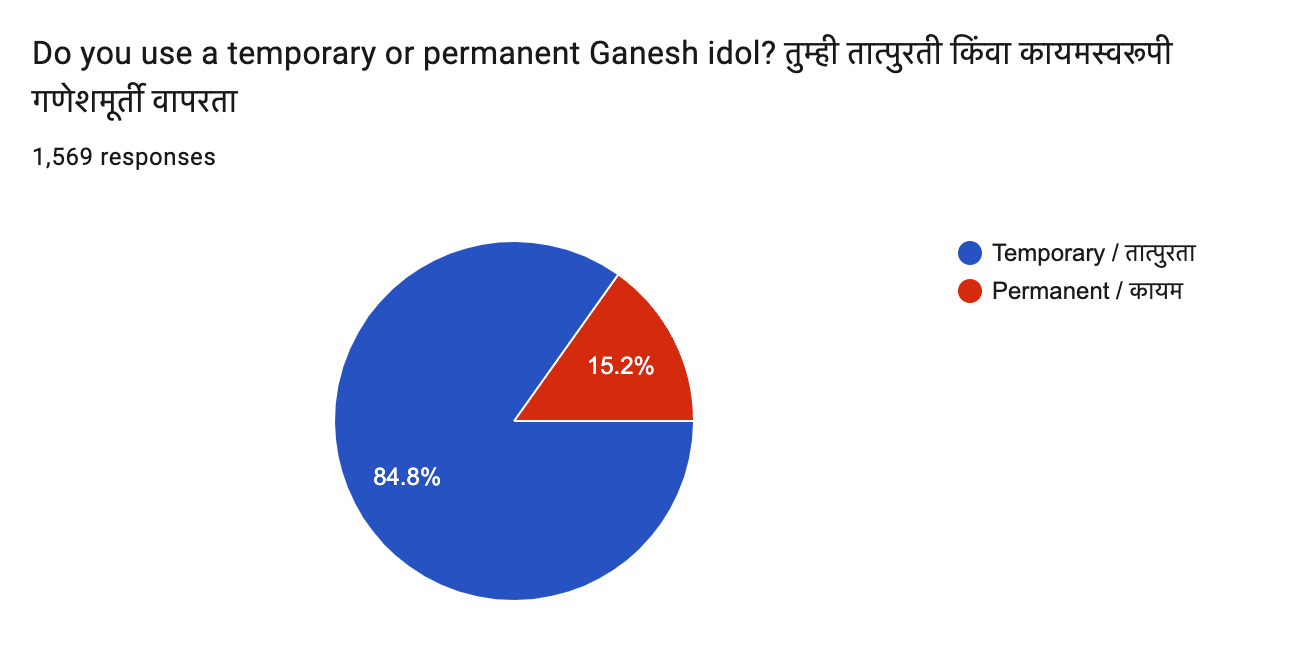

Q2: Do you use a temporary or a permanent Ganesh idol??

Assumption: The shift from the use of a temporary idol to a permanent idol would minimise the need for new idols every year as well as reduce the impact of the immersion ritual on the environment.

Responses: There still seems to be a preference for using temporary idols and this may be based in the belief system and the act of letting go which does not manifest in a permanent idol.

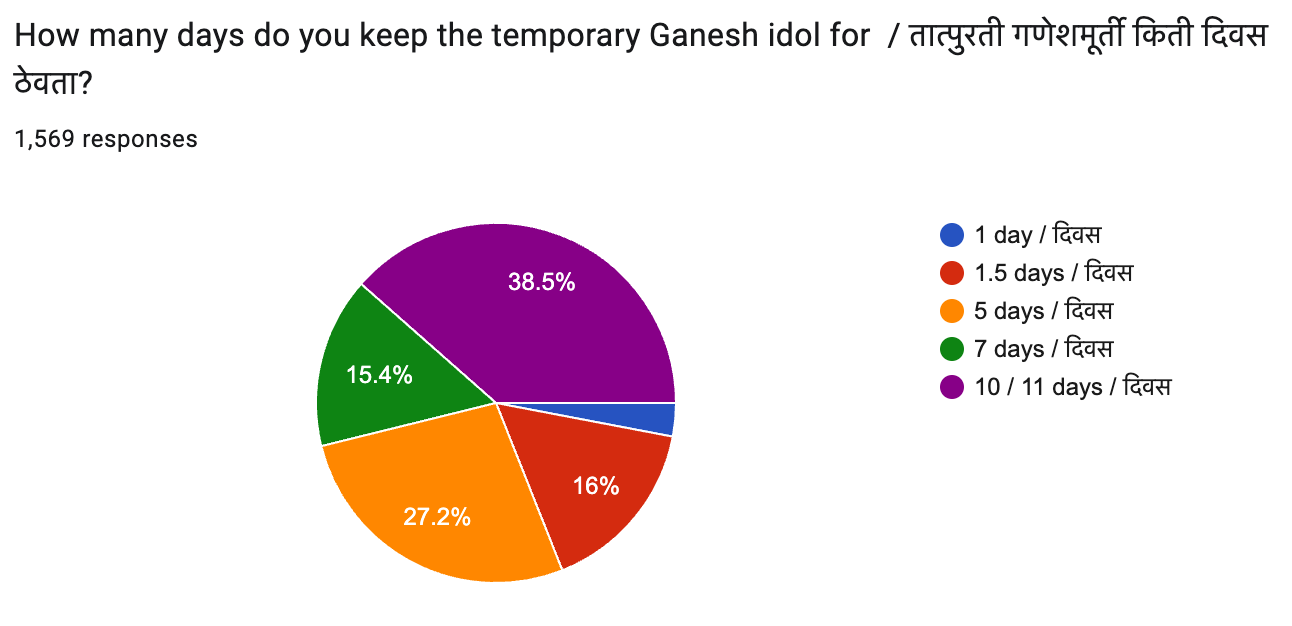

Q3: How many days do you keep the temporary idol for?

Assumption: The duration for which the idol is kept indicates the involvement of the family in the ritual as each day the idol is kept longer results in more activity and work around the ceremonies. As the festival runs over a period of ten days, this would include working days as well and indicate higher social and religious activity during this period. The shift to simplify the ritual would also be relative to the involvement of the citizens in the festival.

Responses: A majority of the respondents celebrate the festival for the entire duration of the festival indicating a higher level of involvement in the ritual.

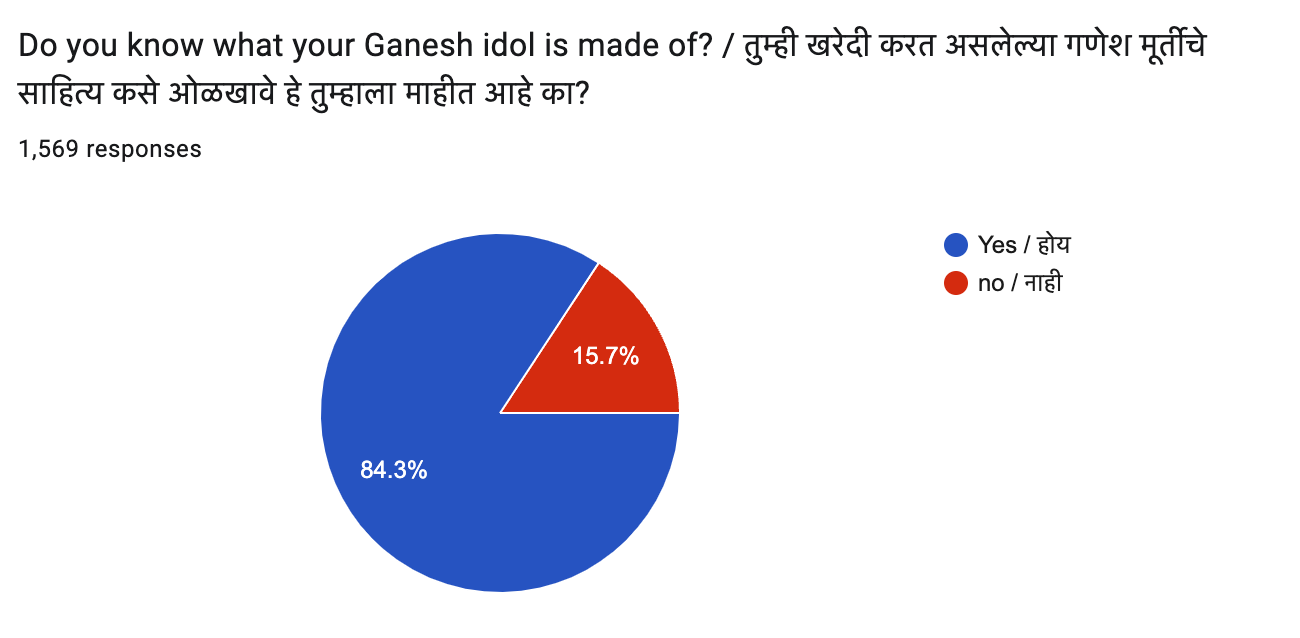

Q4: Do you know what your Ganesh idol is made of?

Assumption: If there is an increasing awareness around materials and the impact of different materials on the natural environment, there would be a more conscious consumption of these materials.

In the past it has been challenging for end users to know exactly what materials and paints are being used in the idols available in the market as this is not indicated on the product. To know the answer to this question they have to proactively ask the vendor which indicates a more conscious consumer behaviour.

Responses: A large majority of the respondents know the material of the idol they use.

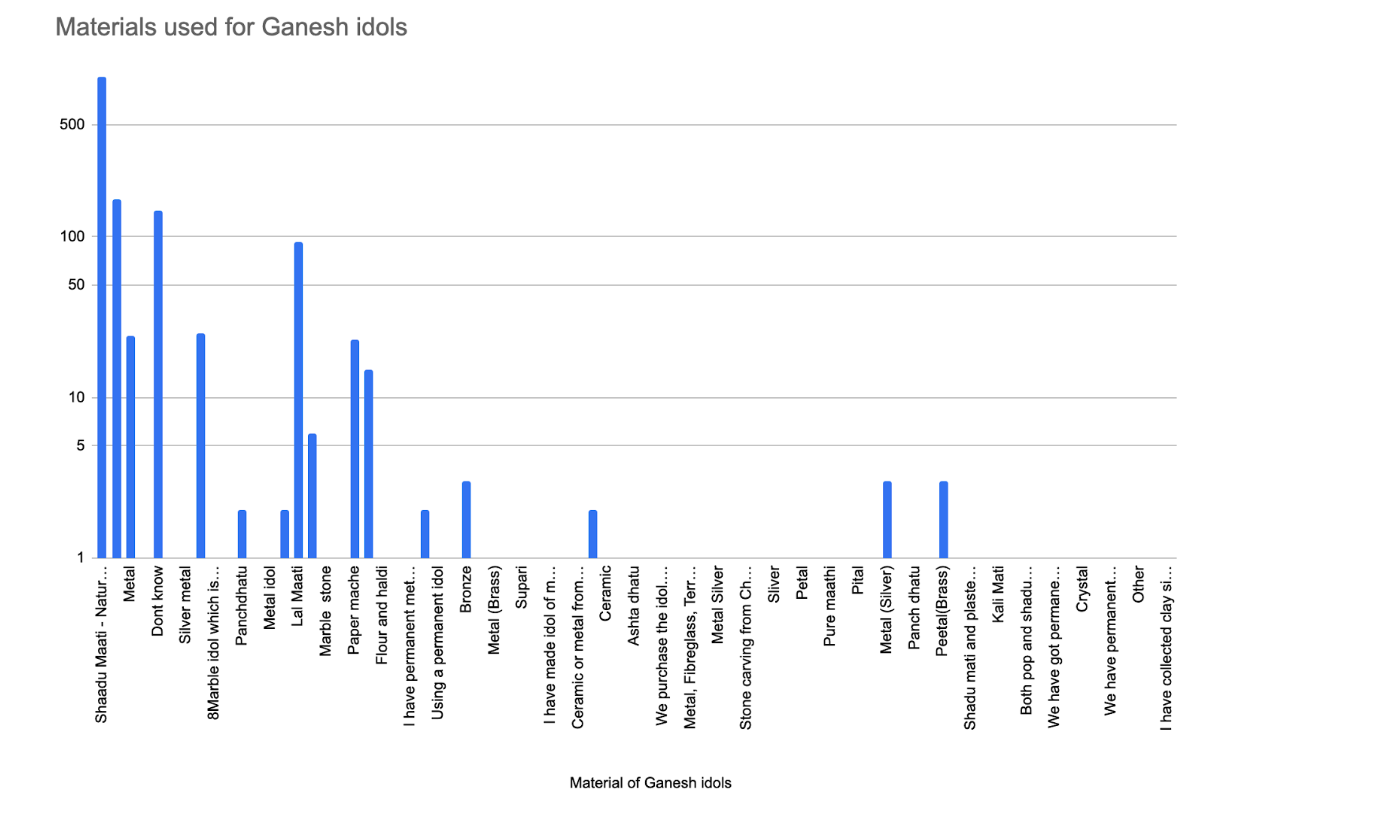

Q5: What material of Ganesh idol do you use?

Assumption: Although there is still a confusion on the exact impact of the various materials available , and the environmental impact relative to each other, in the context of the ban on Plaster of Paris idols , it is important to know what are the other materials being chosen by consumers.

Responses: The range of materials use included the following broadly

Arecanut, Ceramic, Clay, Cow dung, Crystal, Fibreglass, Glass, Metal, Paper mache, Red Earth, Sandalwood, Stone, Terracotta, Turmeric, Wood

These are a combination of temporary and permanent usage. In the case of temporary materials, biodegradability is the main prerequisite and for permanent usage durability is important. Depending on the material , the impact of the immersion of a temporary idol changes.

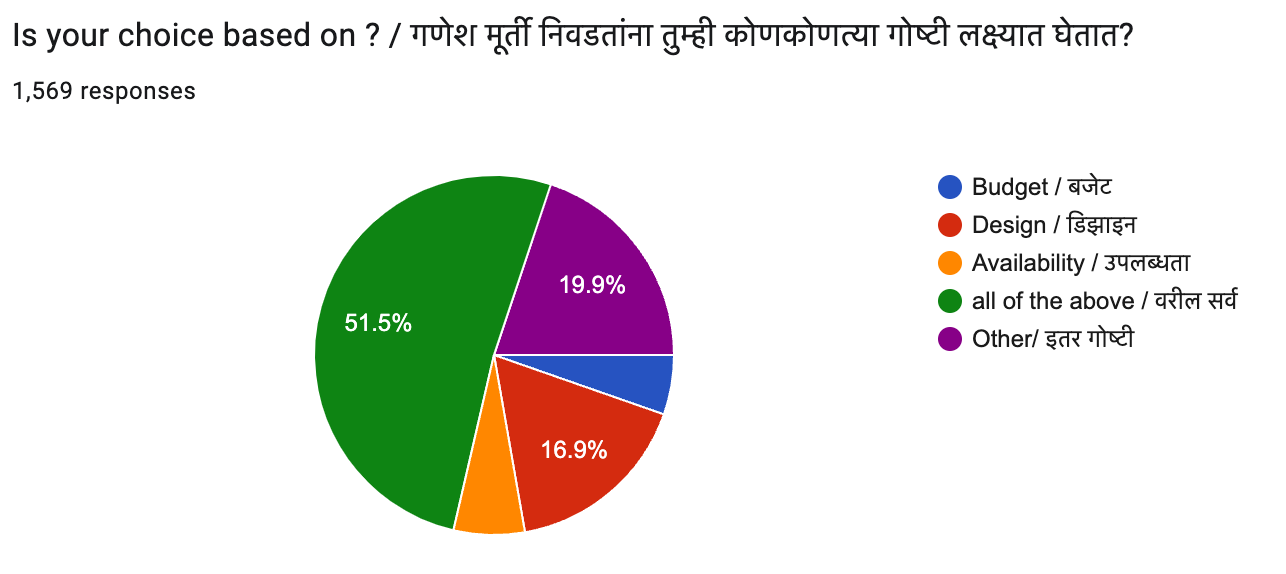

Q6: Is your choice based on budget, design, availability or all of the above?

Assumption: The effort to shift people from toxic chemical materials towards biodegradable materials needs to take cognisance of the financial difference between the two. Materials like Plaster of Paris and chemical paints are significantly cheaper, easier to produce and handle therefore less prone to damage. To make an eco friendly choice may mean that one has to go beyond the budget available and will the consumer make this choice? Also being a religious product, the aesthetic is a big factor in the choice of product and accessibility is also key.

Responses: Over 50% of the respondents cited all three factors as being important to their choices and individually aesthetics and accessibility were more of a concern than budget to the rest.

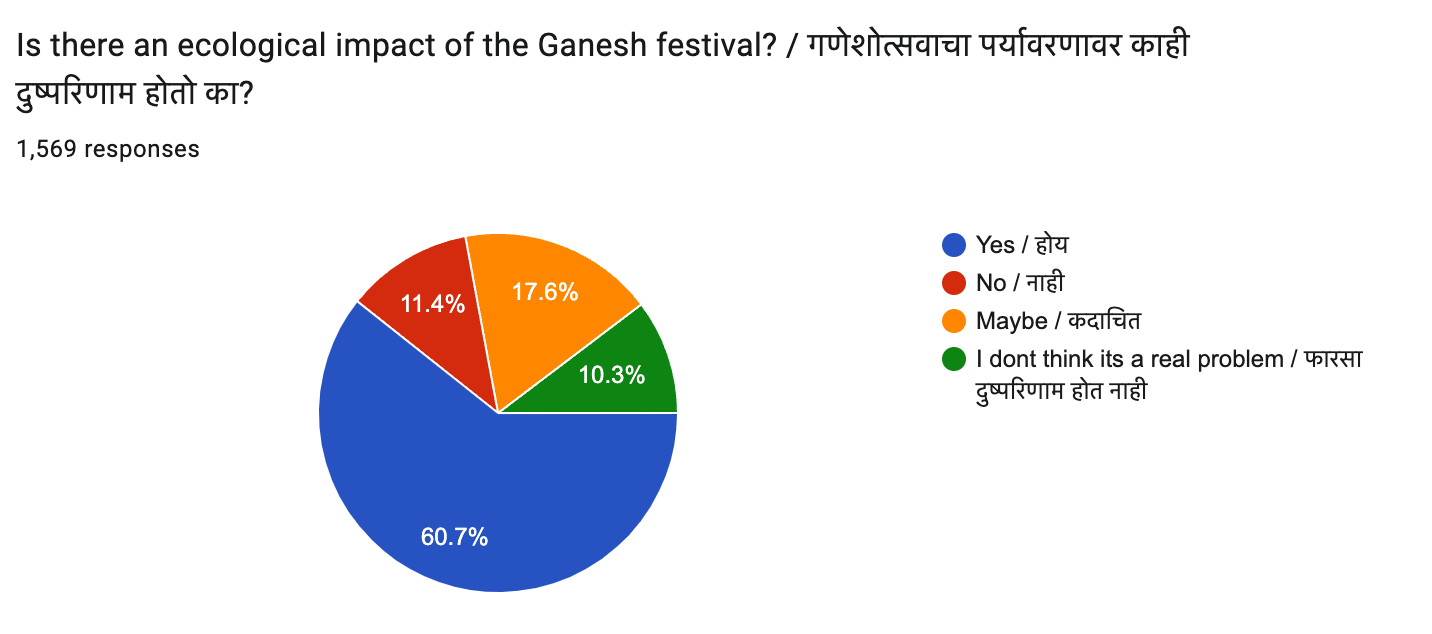

Q7: Is there an ecological impact of the Ganesh festival?

Assumption: Over the past years the awareness levels have risen around the ecological implications of the Ganesh festival. However there is still some disagreement and this basic question was needed to understand to what degree there is still some confusion around the issue.

Responses: While 60% of the respondents clearly said Yes , 11% were clear that there was no impact and those who were unclear added up to a total of 28% . This indicates that the education and awareness raising work is still required.

Q8: Do you buy the idol from the same artisan / shop every year?

Assumption: Traditionally the citizens would pick up their Ganesh idols from the same sculptors each year , forging a bond between the artisan and the user, assuring the artisan of a steady market for his idols as well as creating some degree of influence that a client may have over the artisans choice of material. The break of this bond by modern commercial markets and the increasing industrialisation of the craft has resulted in more chemical materials being used.

Responses: The results were half and half which means that while the original tradition and relationship between artisan and buyer still has not totally vanished it is yet under threat of dissolving .

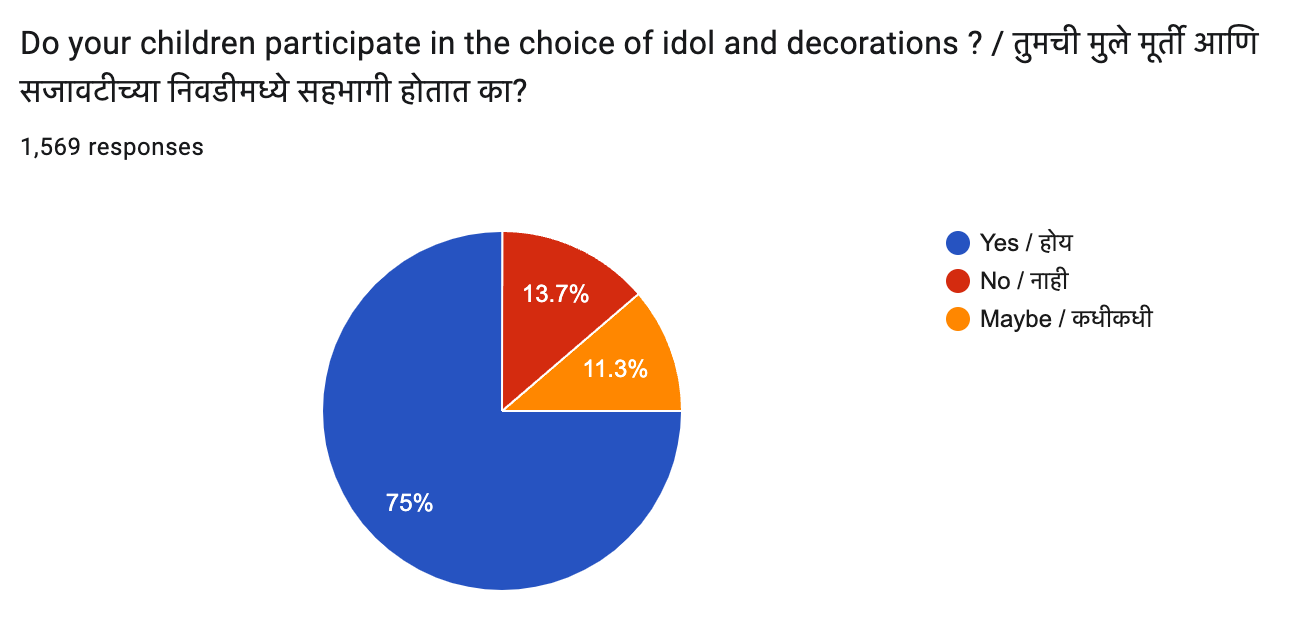

Q9: Do your children participate in the choice of idol and decorations?

Assumption: The Ganesh festival is a tradition that goes down generations in the state of Maharashtra and is celebrated together by all age groups. In most traditional families, the older generations have the final word in the choice of the idols, however when school going children ask for a particular idol, their choice is also respected. With an in reading education around the material impacts, children have started to demand eco friendly choices from their parents.

Responses: 75% of the respondents replied positively to this question indicating that children can influence the decision made by the parents significantly.

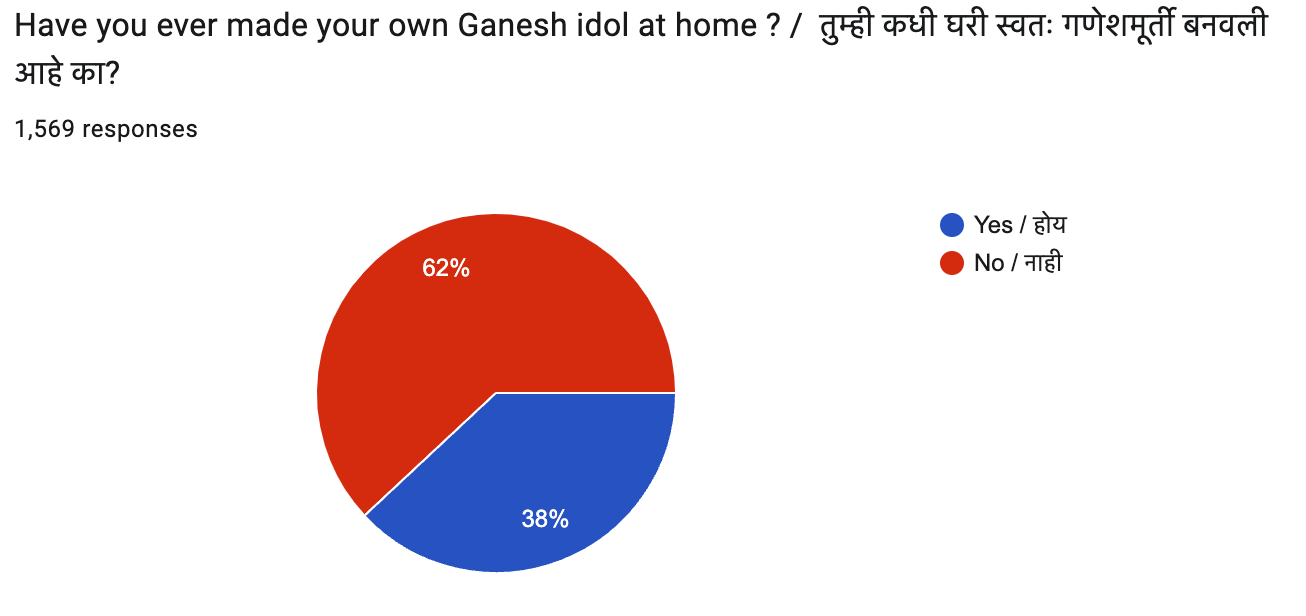

Q10: Have you ever made your own Ganesh idol at home?

Assumption: The act of making ones own Ganesh idol is still followed in South India where this practise is considered an important part of the expression of devotion. By handling the material oneself one can be more aware of the nature of the materials being used and the challenges faced by the artisans while producing them.

Responses: Only 38% of the respondents said that they did make the idols themselves which means that the larger majority is simply buying the idol from artisans.

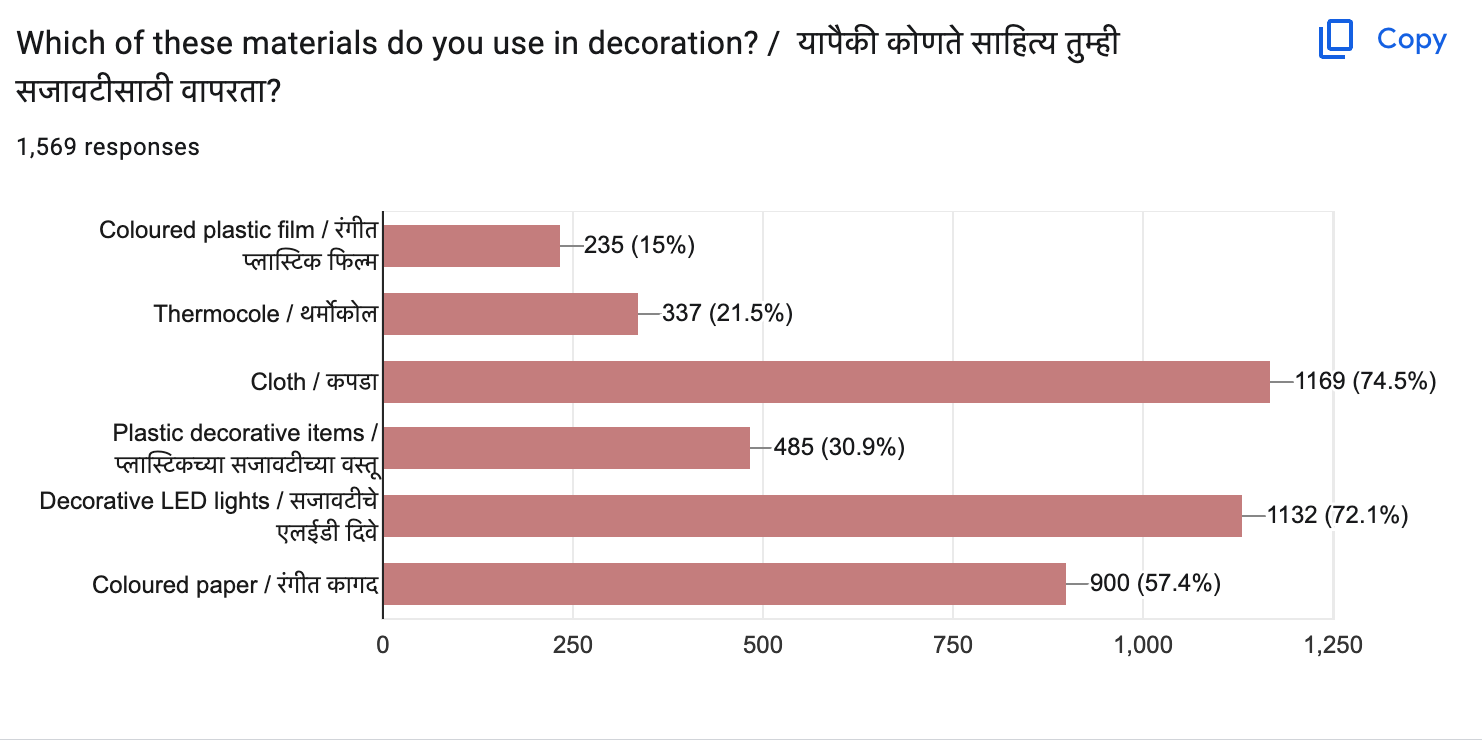

Q11: Which materials do you use in decorations?

Assumption: While sculpting an idol themselves may be difficult for most families , they do take great pleasure in decorating the idol and the altar for worship. In the choice of the materials they use for this one could also sees their inclination towards a zero waste festival.

Responses: Plastic film, plastic decor and thermocole continue to be part of the materials used for decorations in spite of the ban on these substances.

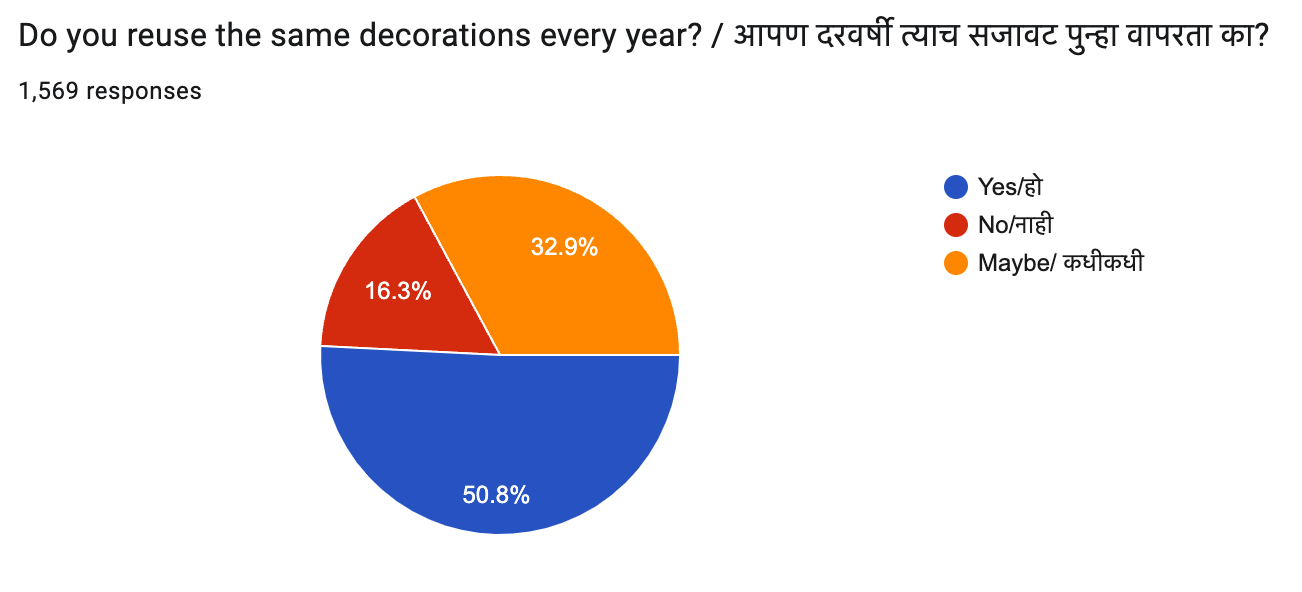

Q12: Do you reuse the same decorations every year?

Assumption: The habit of reuse is a tradition in most Indian families especially in those from lower economic stratas. This idea of reuse may sometime be in conflict with the belief that worship should only be done with fresh items. Yet although the idol is freshly bought each year, there may be a willingness to reuse decor and design it differently each year.

Responses: Materials like plastics lend themselves to reuse and it seems that over 50%of the devotees do reuse their decorations.

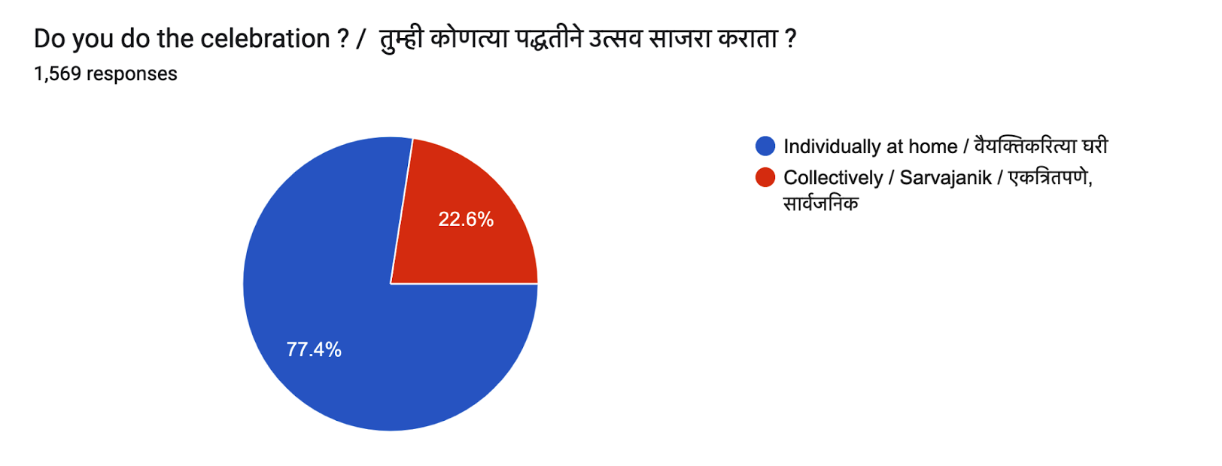

Q13: Do you do the celebration individually at home or sarvajanik, collectively?

Assumption: The idea of one idol for several thousand people in one locality was what Bal Gangadhar Tilak wanted to encourage for community to come together and celebrate collectively – this significantly reduces the ecological impact of the festival as well.

Responses: 77.4% said they preferred to celebrate individually – this may be also because the nature of the sarvajnik festival shifts the focus from a more spiritual religious event to a social celebration .

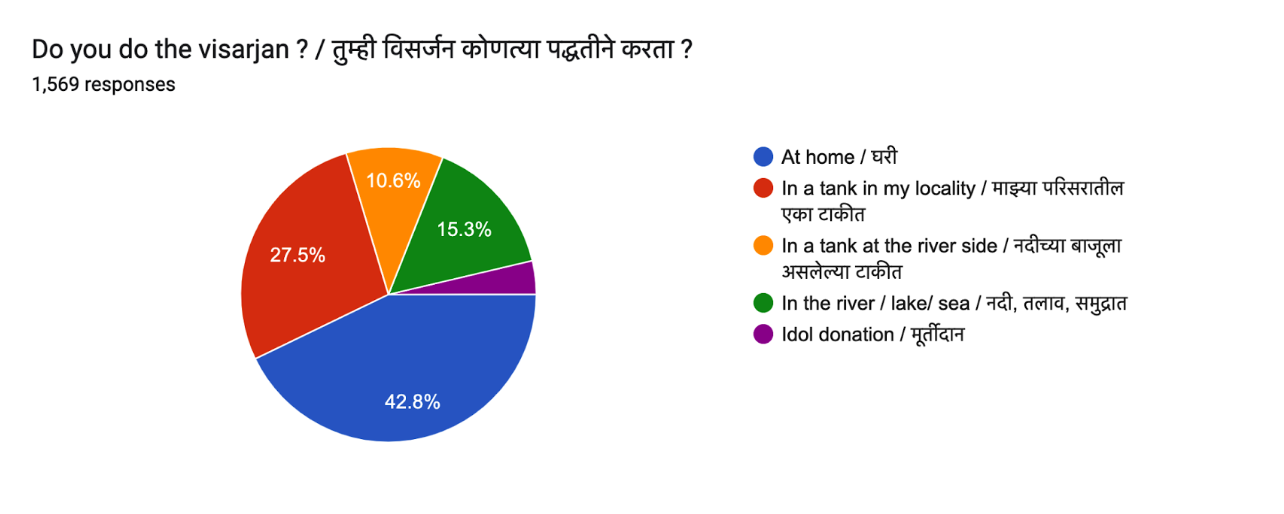

Q14: How do you do the visarjan / immersion?

Assumption: As the immersion is the primary cause of water pollution the preferences around the immersion are key. Home immersion , immersion in a tank in the same locality or at the river banks, immersion into the natural water bodies or no immersion at all are the options available.

Responses: 42.8% chose to do the immersion at home followed closely by a tank in the locality. Bringing the idol out of the house and symbolically offering it back seems to be important to the farewell of the idol. Similarly some people still prefer to make the pilgrimage to the river banks even if they choose to put it into a tank there whereas a concerning 15% are still choosing to immerse their idols in a natural waterbody.

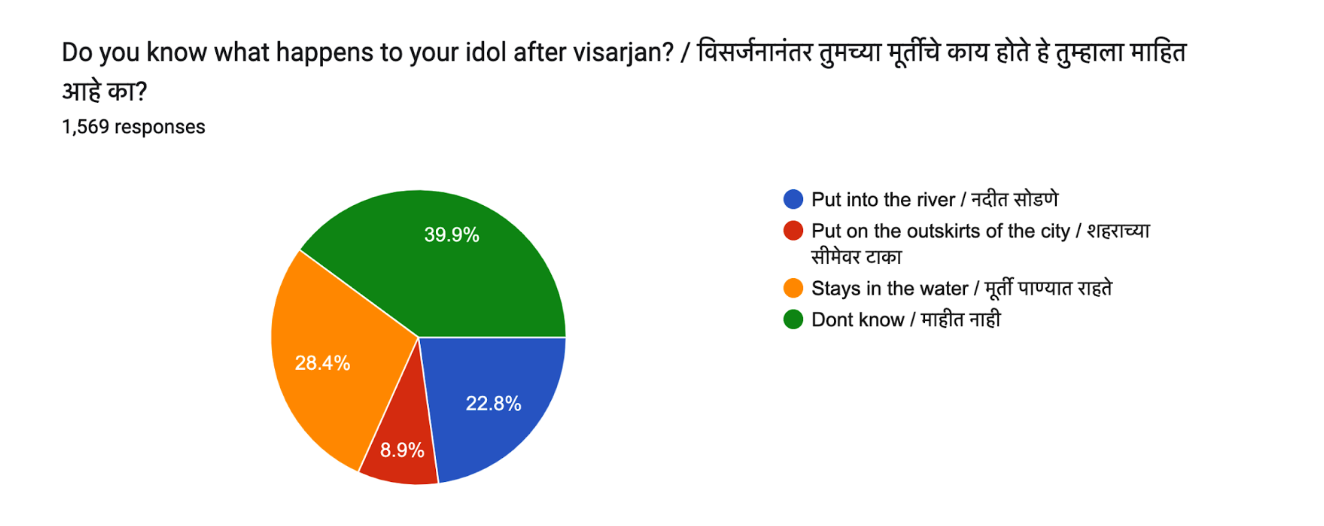

Q15: Do you know what happens to your idol after visarjan / immersion?

Assumption: Our of sight out of mind is usually the case in waste management especially in cities where urban residents know little about how the waste they create is disposed off by the government. A decade ago when photos of the post visarjan mess were publicised there was outrage around the situation. Can raising awareness of the final journey of the idol after visarjan make people more aware about the impact of their celebrations ?

Responses: Nearly 40% of the respondents state that they don’t know what happens to their idols after immersion. 22.8% believe they are all out into the river and 28% believe they stay in the waters. Only around 9 % have some inkling about the idols being sent to mines outside city limits.

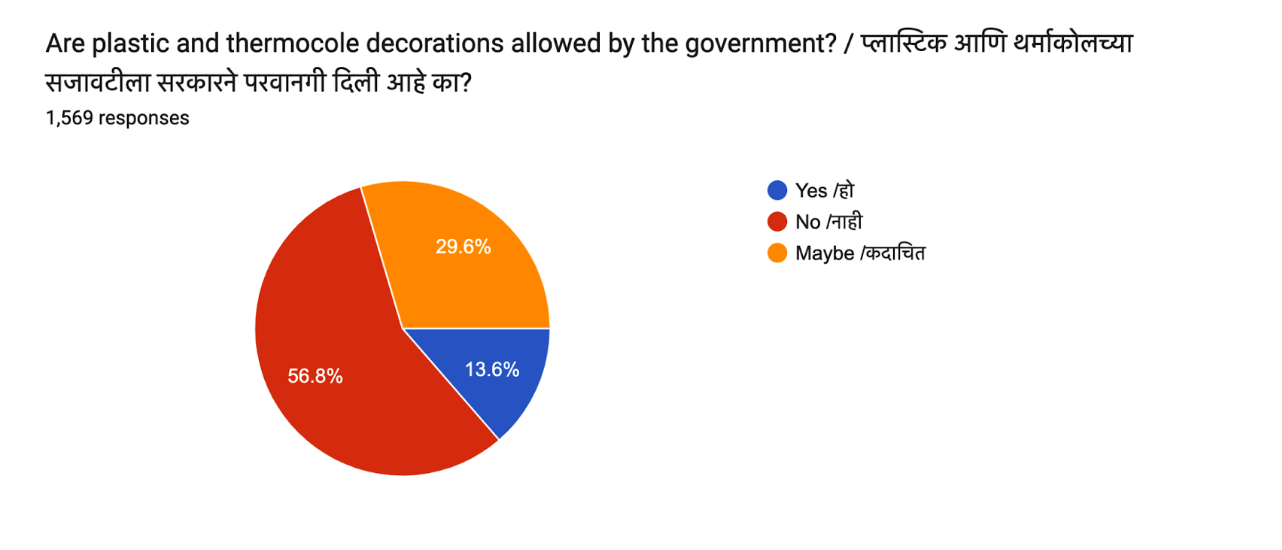

Q16: Are plastic and thermocole decorations allowed by the government?

Assumption: The ban in 2020 established by the Pollution Control Boards have not been implemented fully nor have they been adequately publicised. What is the level of awareness around this ban?

Responses: 56.8% correctly identified that plastic and themocole has been banned – only 2 years prior a similar ban on single use disposables may have made this one easier to digest. The remaining 44% is still unsure of the ban.

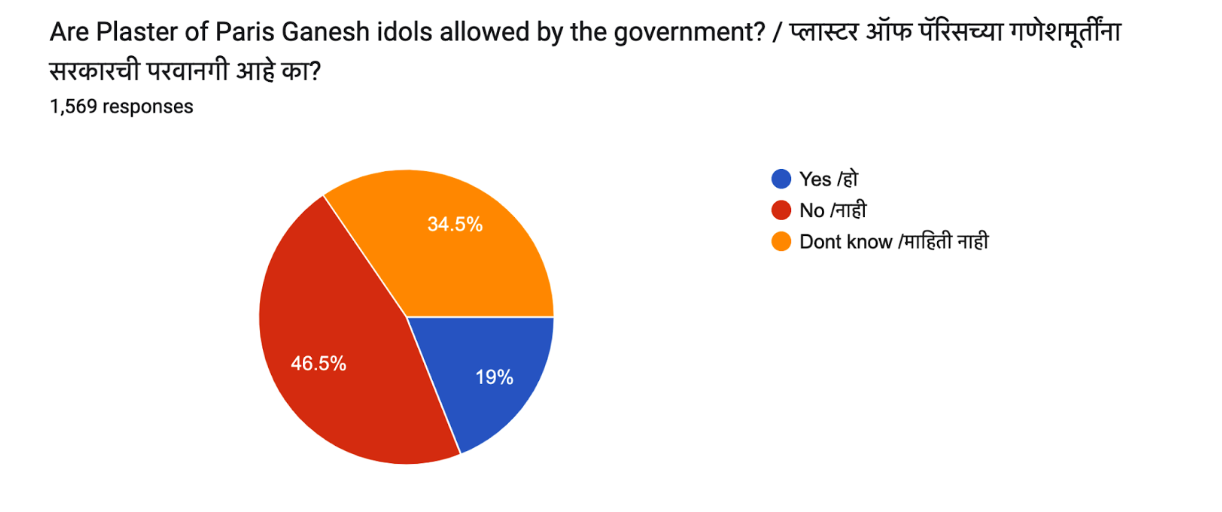

Q17: Are plaster of paris idols allowed by the government?

Assumption: The ban in 2020 established by the Pollution Control Boards were focussed on the immersion of POP idols but were not very clear about production and sale of thes same. The inability of the government to implement this ban has also led to confusion around the exact status of the ban on POP.

Responses: 46.5% correctly identified the ban on POP yet the majority balance either did not know or thought that there was no such ban.

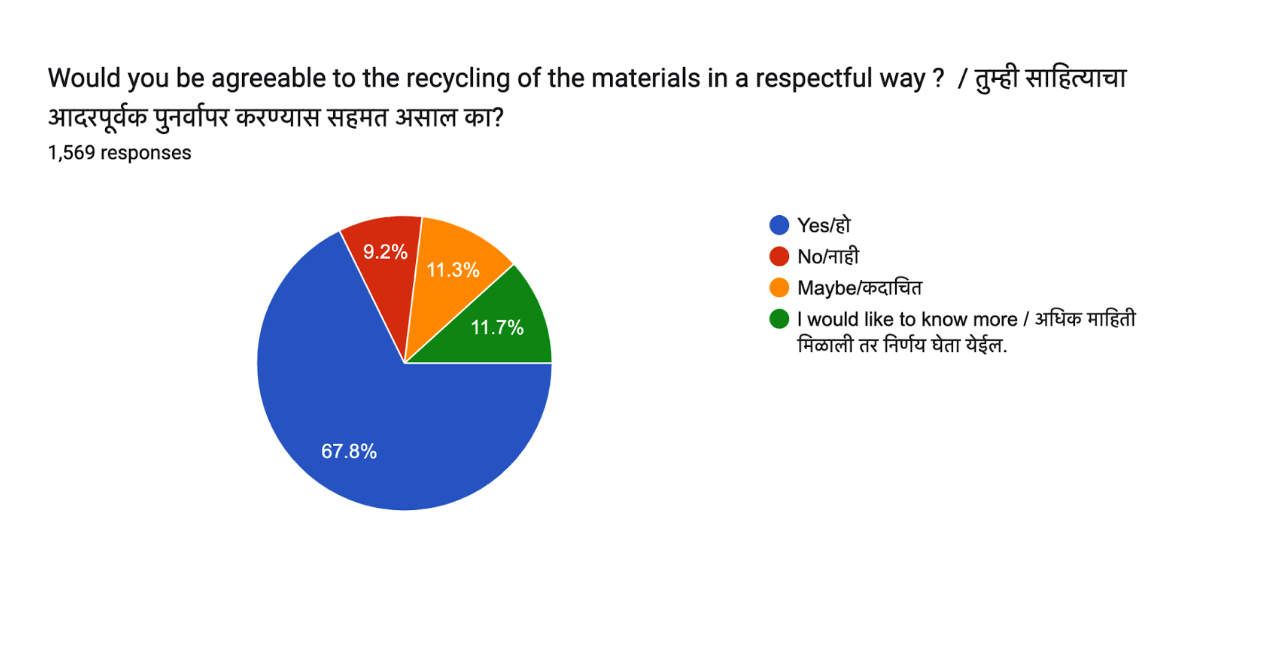

Q18: Would you be agreeable to the recycling of the materials in a respectful way?

Assumption: Almost 15 years ago when the idea of donating and recycling the POP Ganesh idols was first floated by some youth groups in Pune, there was a strong backlash by some sections of society. With the growing awareness around the festival, is there an openness to recycling now?

Responses: 68% of the respondents replied positively – this is a very encouraging shift and around 24% of the balance are somewhat open to the idea. 9.2% refused the idea of recycling and this resistance needs to be studied and understood better.

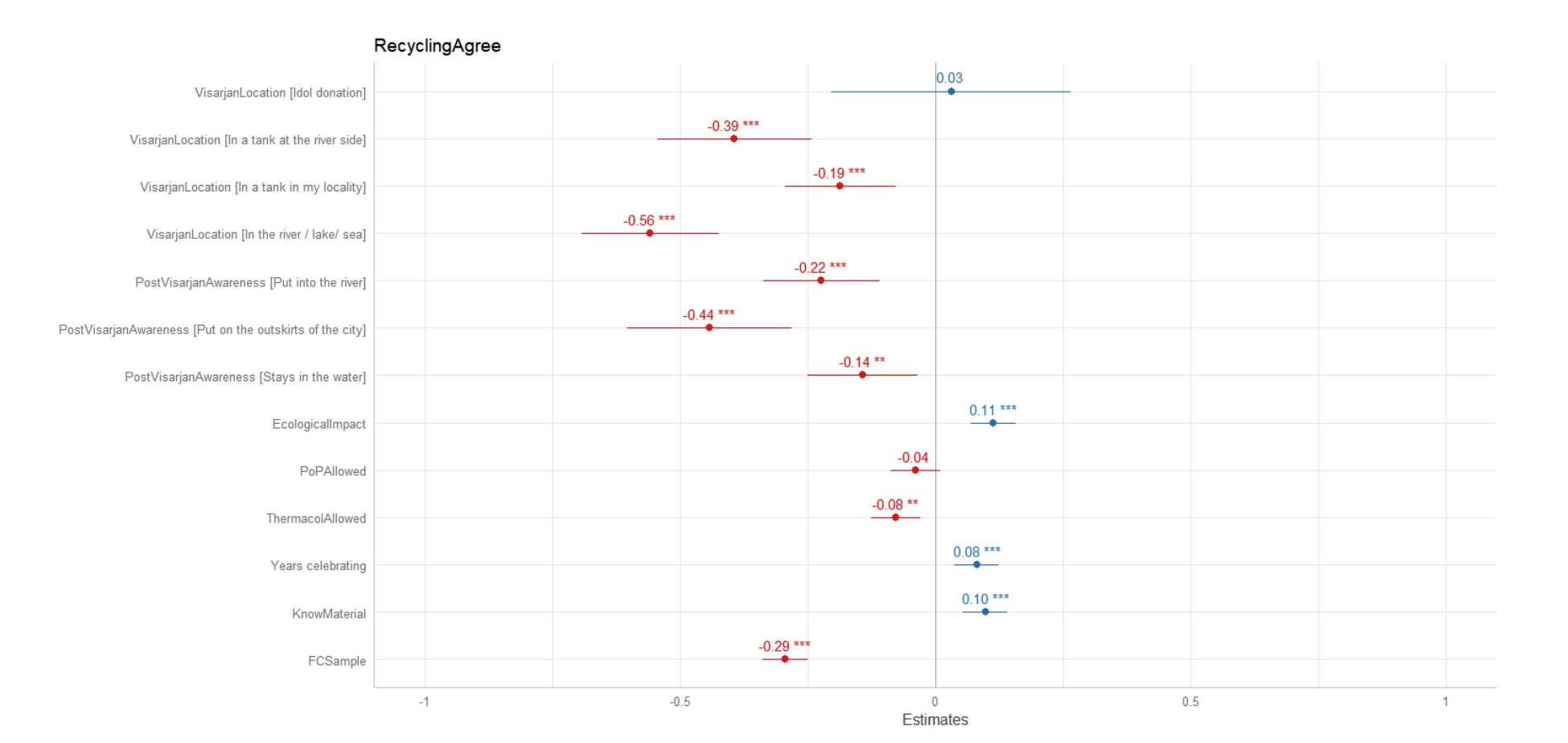

DATA ANALYSIS AND CORRELATIONS by Dr Sonya Sachdeva

In the analysis done by Dr Sonya Sachdeva, we posed a few questions to understand what might affect the willingness of respondents for or against recycling . The following questions were considered in her study.

- What is the level of confusion around the POP ban and thermocol ?

- What is the link between going to the river for visarjan and openness to recycling ?

- How many people are open to recycling materials respectfully?

- Where is the resistance coming from whom ? and why ?

The variables considered were

- The visarjan location

- The post visarjan awareness levels

- The understanding of ecological impact

- The awareness of the ban on POP and Thermocole

- The number of years celebrating

- The awareness of materials

- The use of permanent idol

- The relationship with the same artisan

The samples from the Fergusson college students ( which were more focussed on typically Maharashtrian population ) were also compared to the rest to see if they showed a significant change.

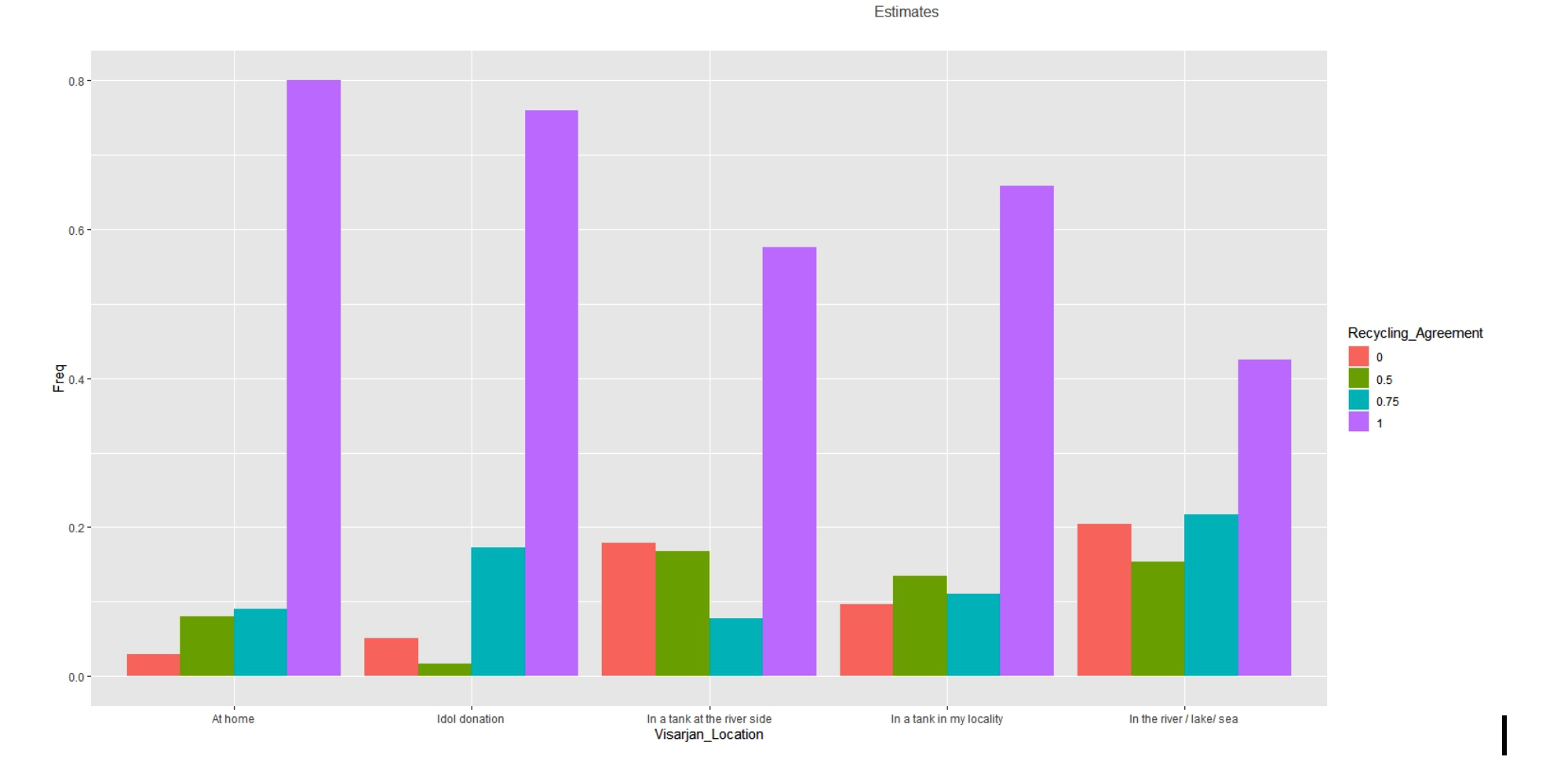

The first graph shows model estimates predicting recycling agreement on a standardized scale so you can compare across variables to get a sense of the magnitude of effect. Variable effects noted in blue increase recycling agreement whereas those noted in red decrease recycling agreement. The most predictive variable for recycling agreement/disagreement is the FC Sample. So, the more traditional households (in Maharashtrian localities) are least likely to agree with recycling the murtis. This is followed by Visarjan Location as the second most predictive variable. People who do visarjan in a river/lake/sea or on the outskirts of the city are least likely to agree to recycle the murtis. Knowing whether thermocol is allowed is also related to recycling — with people who say that thermocol is allowed, less likely to agree with recycling.

On the positive side, knowledge of the material of the murti is generally aligned with pro-recycling intention as is the knowledge of ecological impact and years celebrating the festival.

The visarjan location and FC student sample variables point to where resistance may be coming from. People who are used to doing visarjan at a location other than at home are less likely to agree to recycle the murti. Traditional households (from the FC sample) are also less likely to agree to recycling. However, it is also important to note that the majority of respondents in this survey (second graph) already do the visarjan at home so we’re just talking about variability in degrees.

Dr. Sonya Sachdeva is a computational social scientist with the US Forest Service in the greater Chicago area. Sonya also has an adjunct appointment with the Environmental Policy & Culture program at Northwestern University. She holds a Bachelors in Economics from the University of Michigan and a doctoral degree in Cognitive Science from Northwestern University. Her current projects involve large-scale automated text analysis of climate change coverage in the media, field assessments of the efficacy of environmental programs and behavioural experiments to study the impact of resource scarcity on conservation behavior. She has been guiding research surveys and data analysis carried out by eCoexist on various projects and was the primary guide for the survey done on the Punaravartan campaign.